Large Parathyroid Adenoma (June.2020)

Case presentation

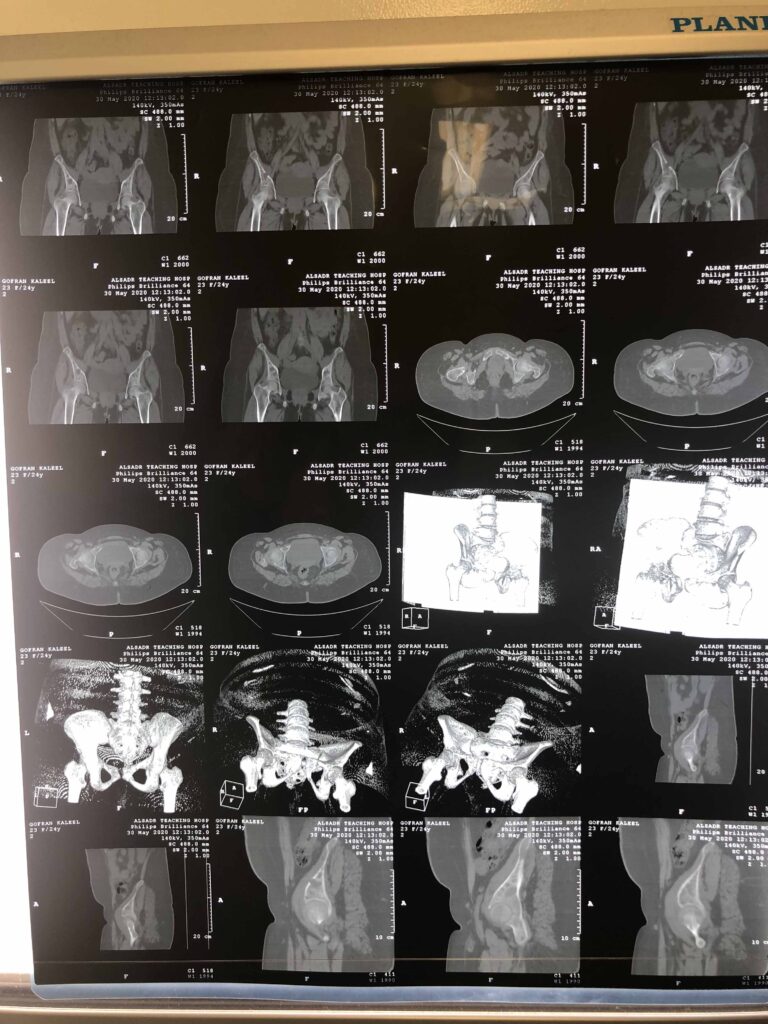

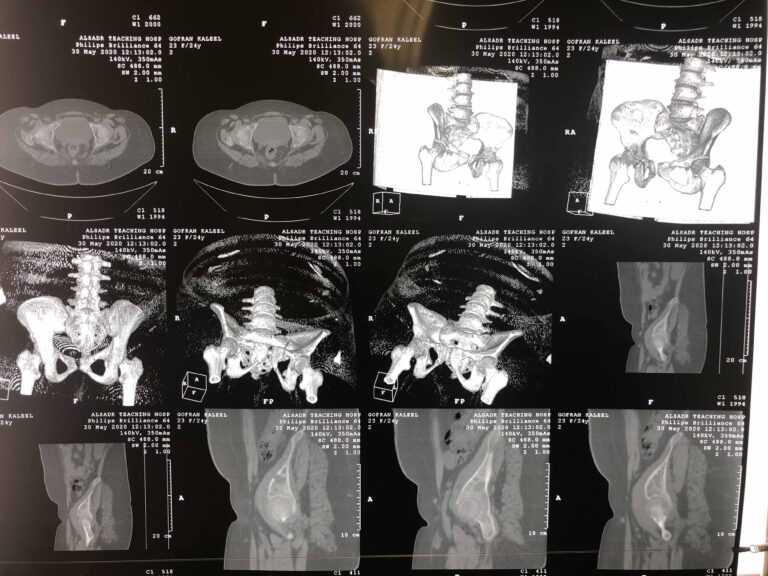

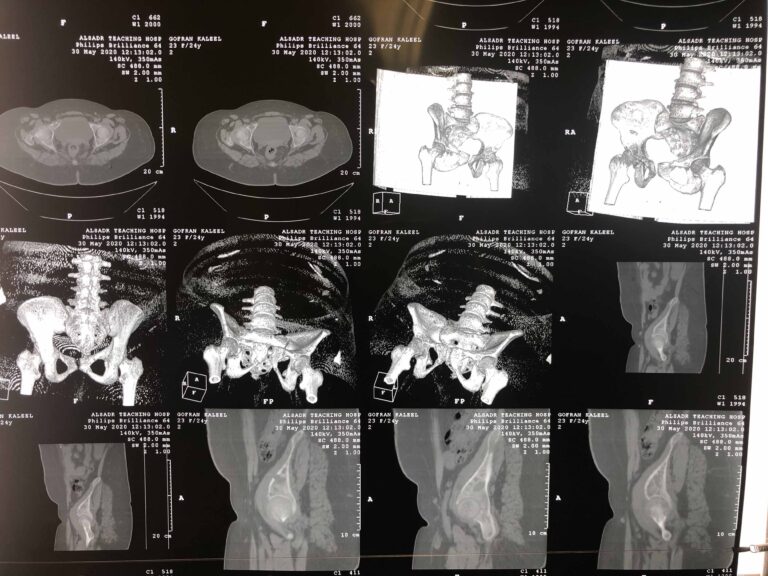

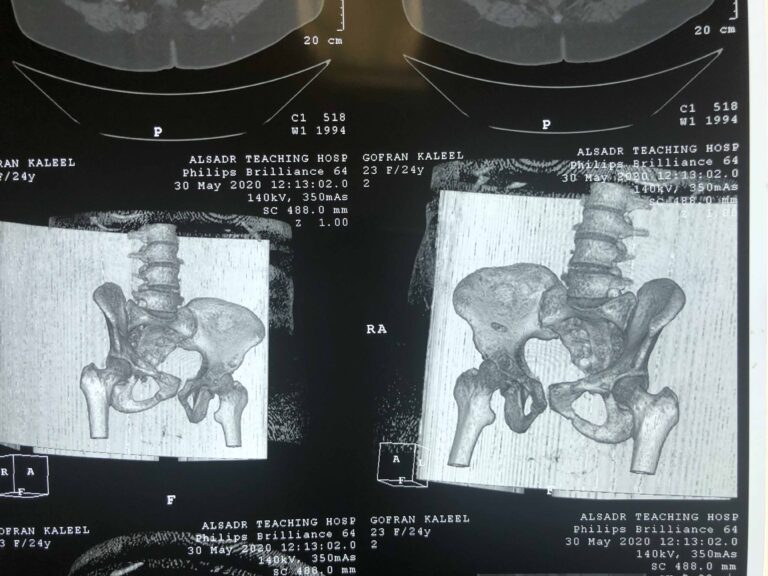

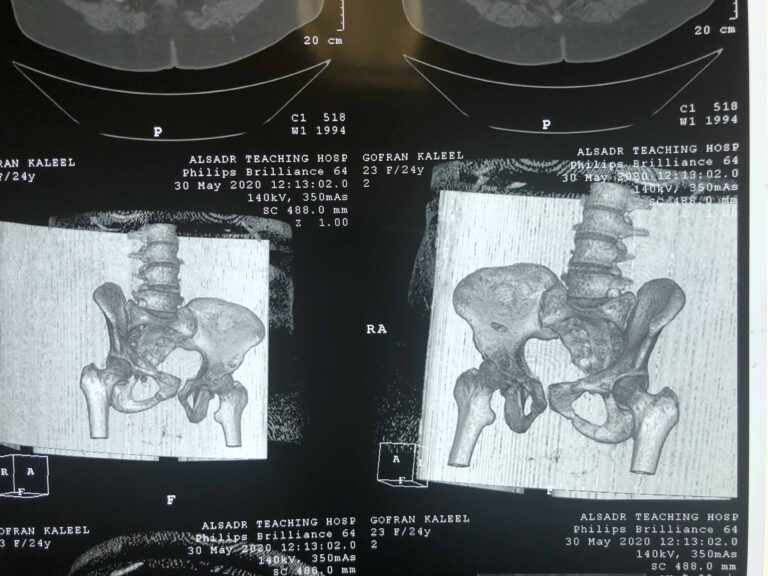

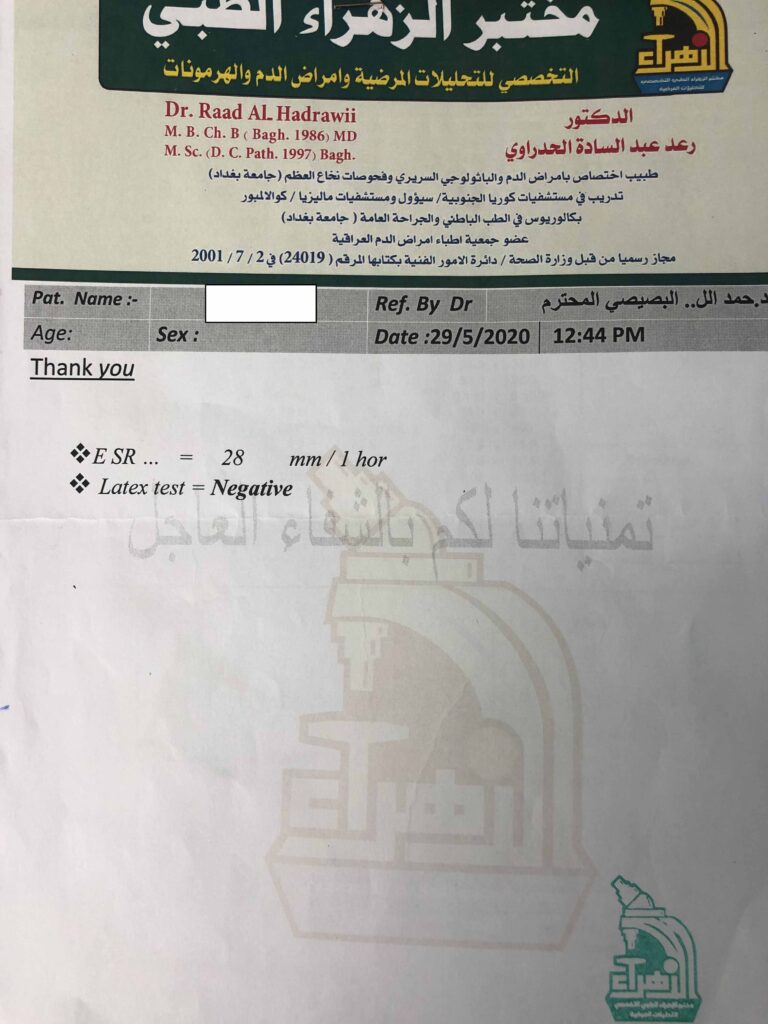

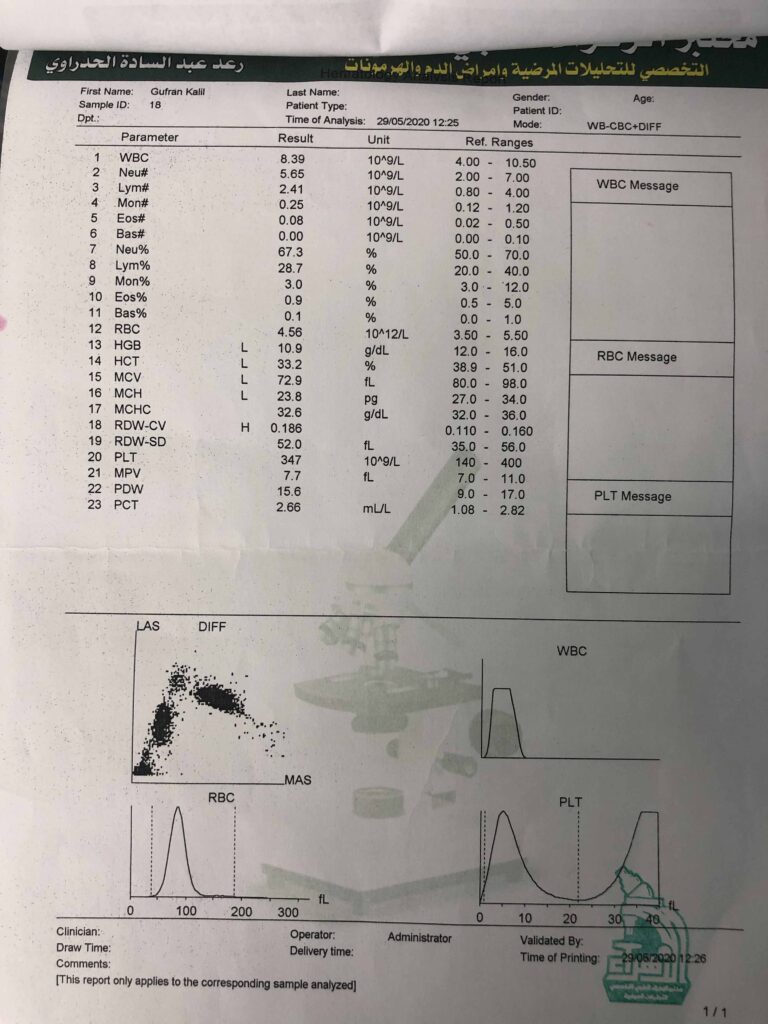

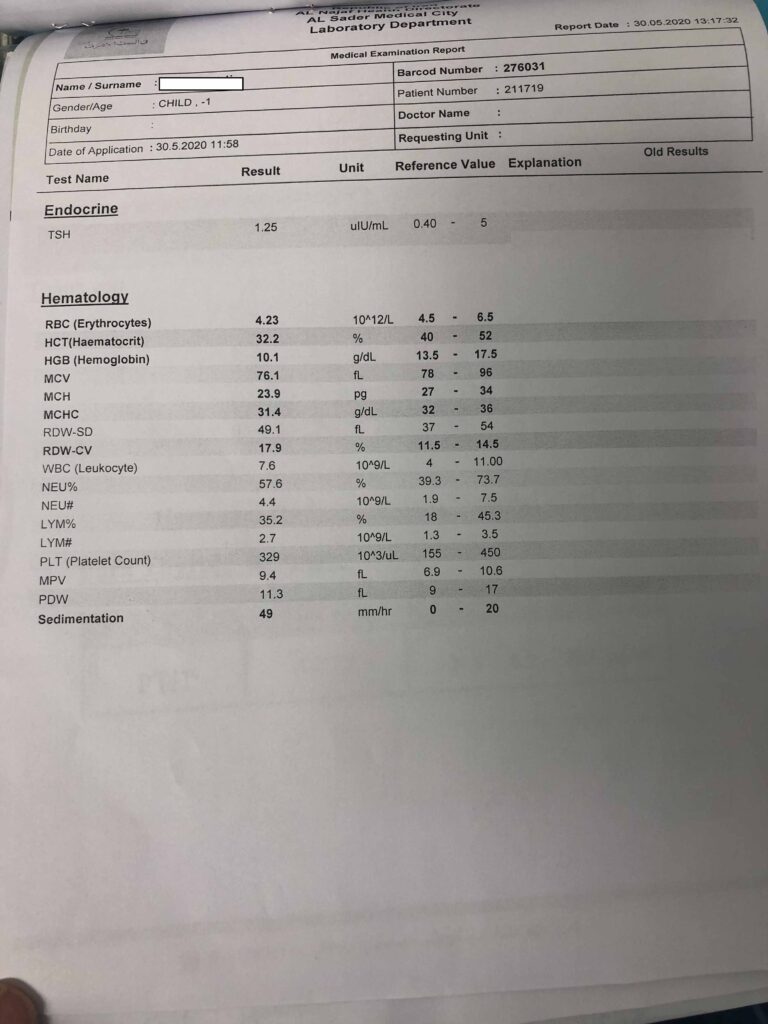

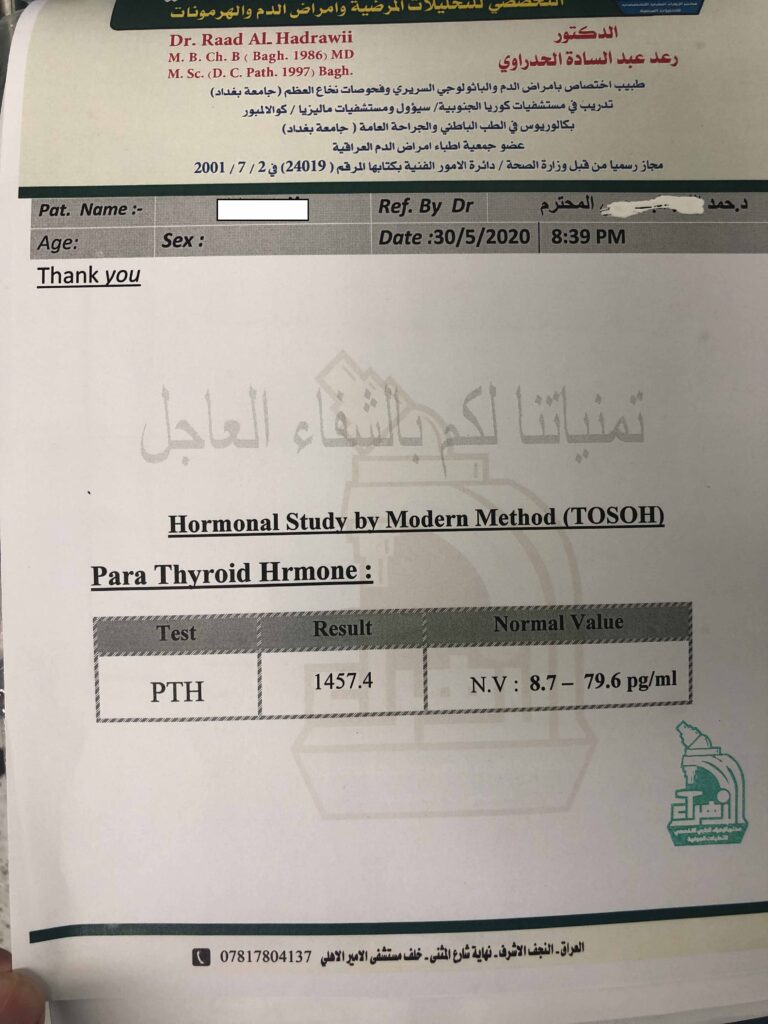

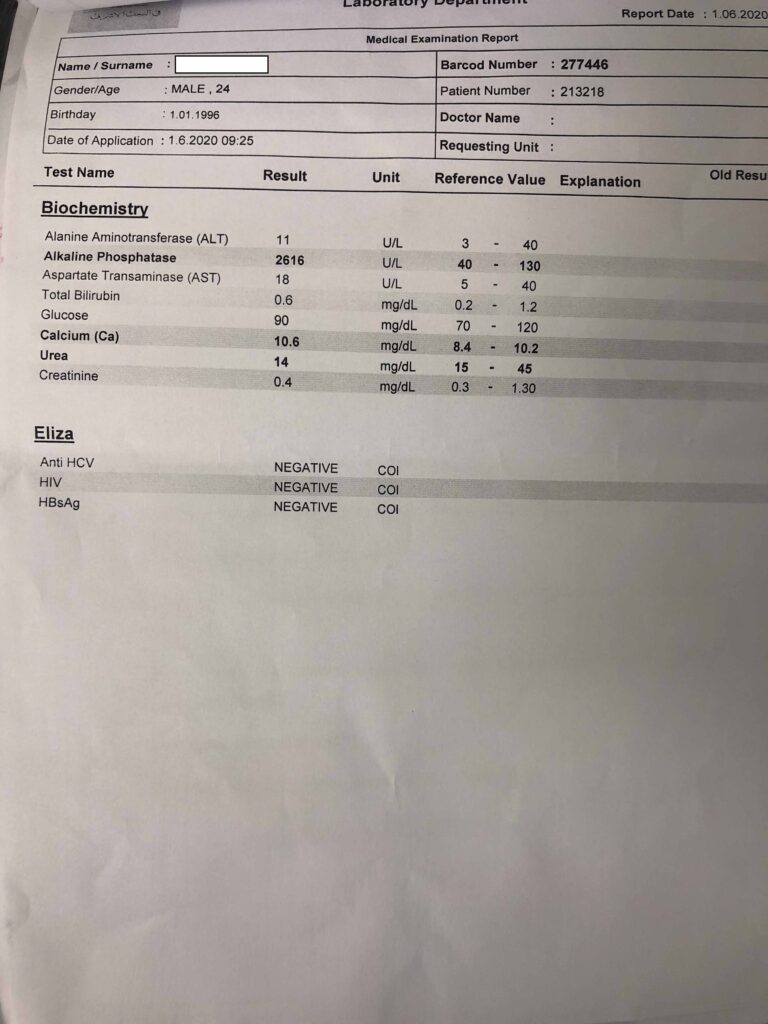

A 24-year-old Iraqi woman presented with a pelvic fracture to the orthopedic surgeon. Plain x ray and CT scan of abdomen and pelvis done. On investigations there was very high parathyroid hormone. So diagnosed as a case of primary hyperparathyroidism and referred to me for further management.

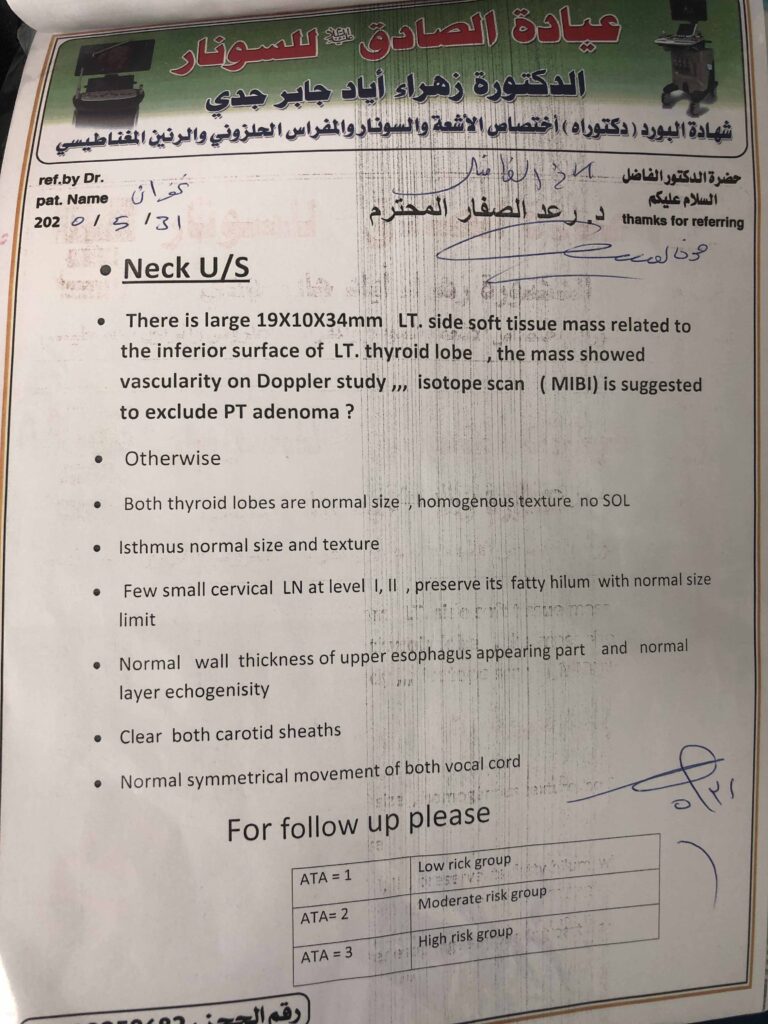

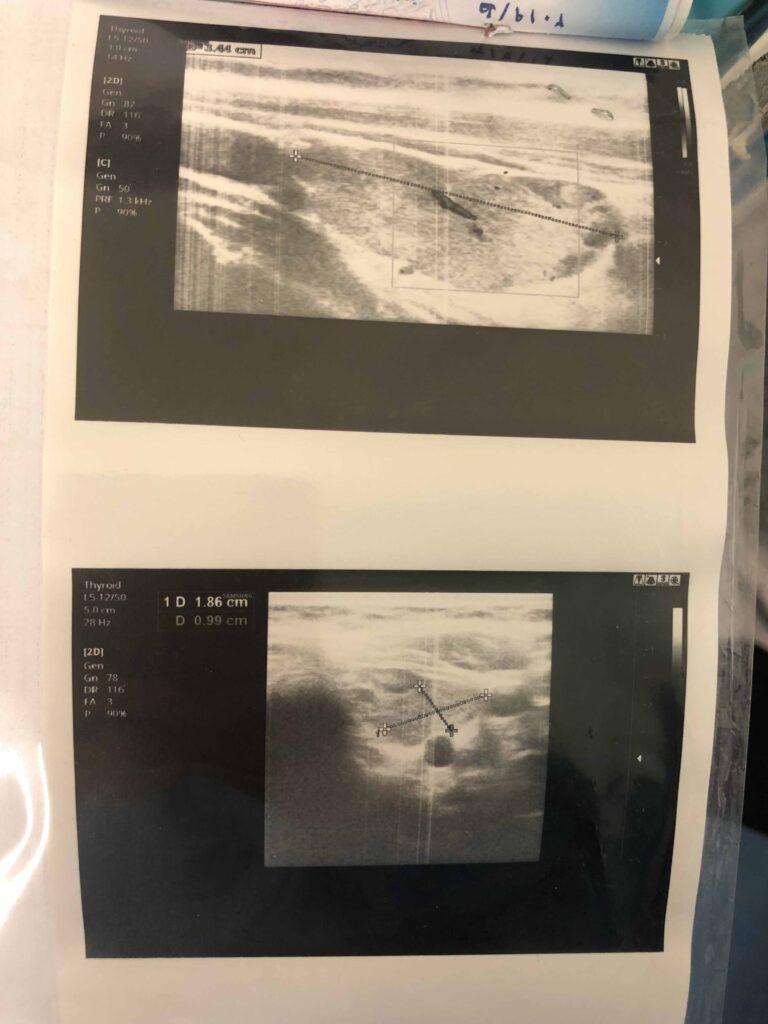

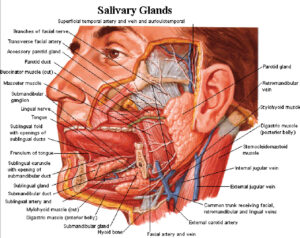

On presentation: the patient young female on wheel chair with palpable right-sided neck mass and generalized fatigue. Investigations revealed hypercalcemia with elevated parathyroid hormone and an asymptomatic kidney stone. Ultrasound of the neck showed a large left side soft tissue mass 19*10*34 mm related to inferior surface of left thyroid lobe with increased vascularity on Doppler.

Clinical and laboratory review for SARS – COV-19 was negative. However all precautions for SARS – COVID-19 were taken during operation.

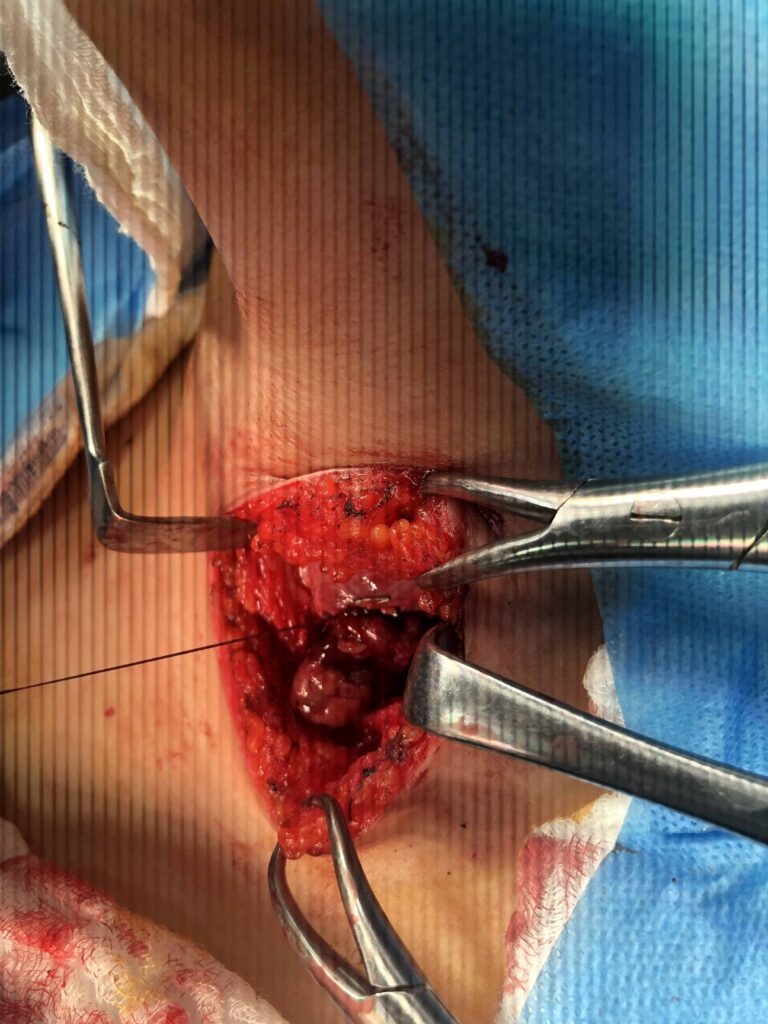

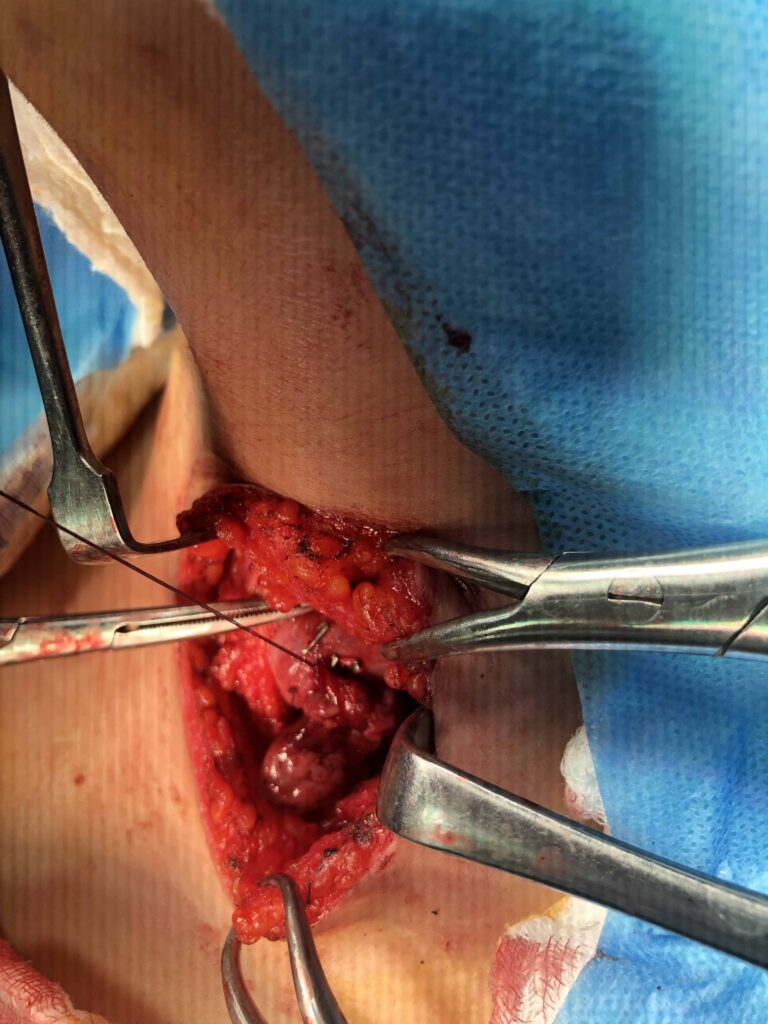

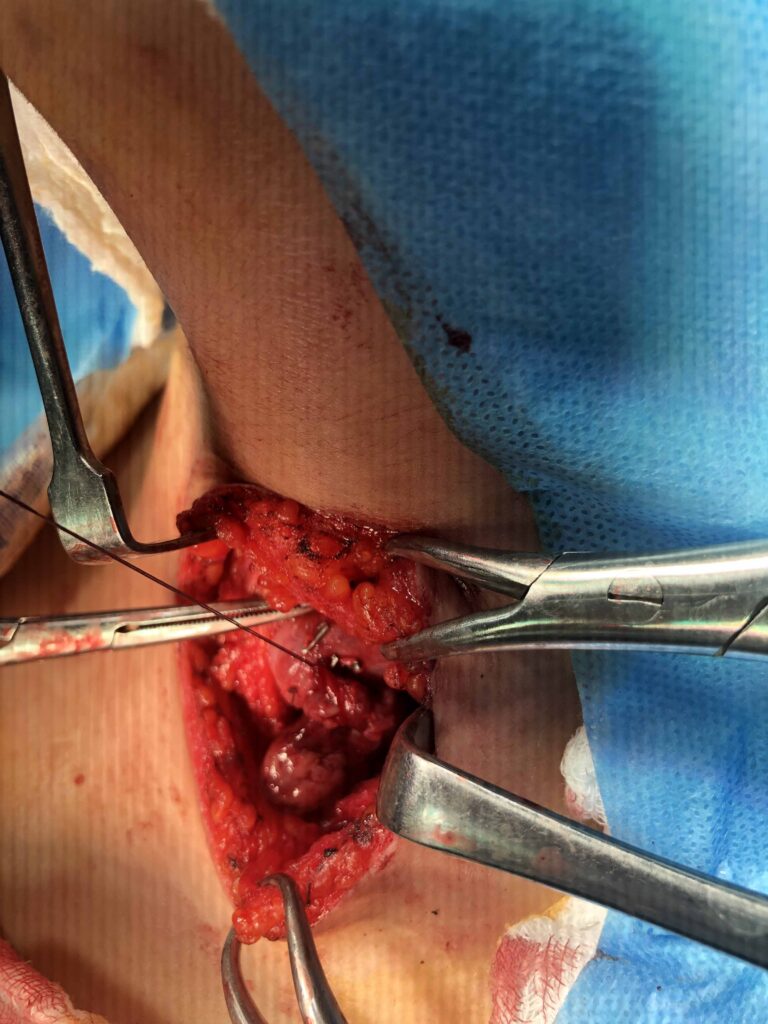

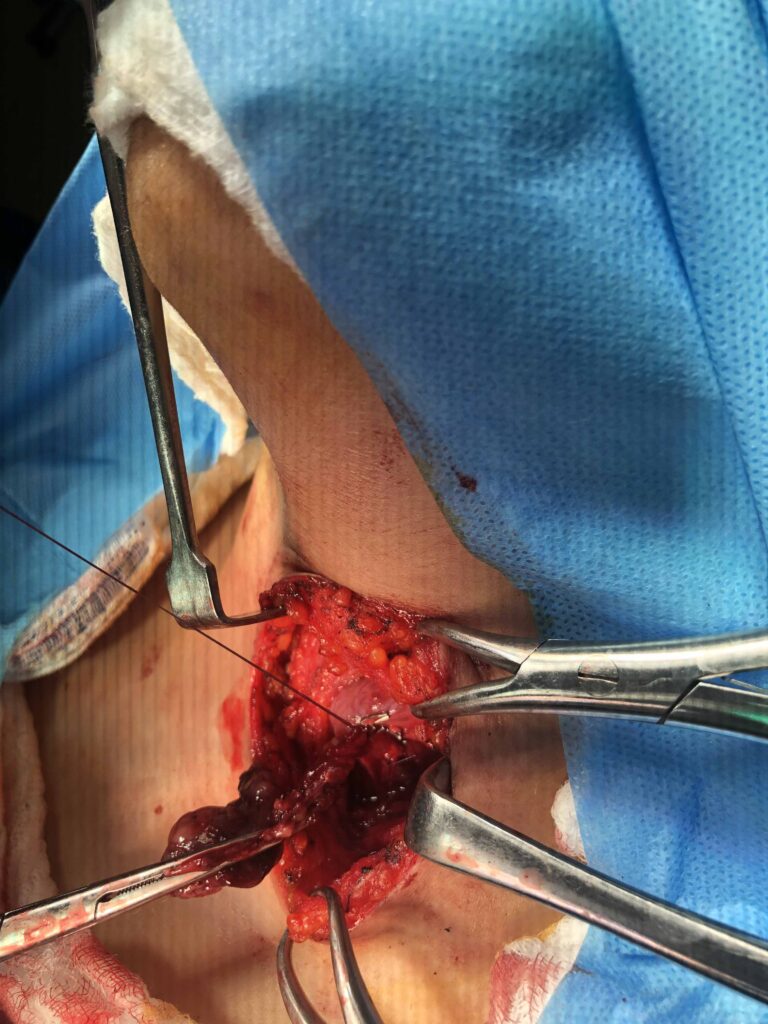

Focused surgical neck exploration was done and a large left sided parathyroid adenoma was excised.

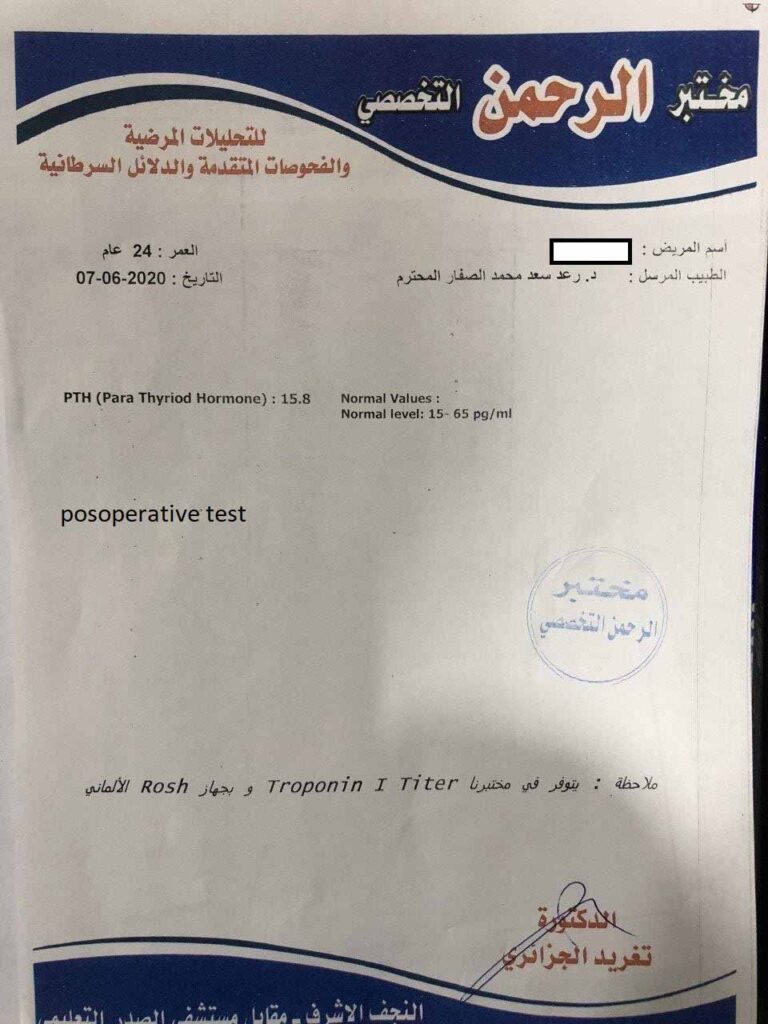

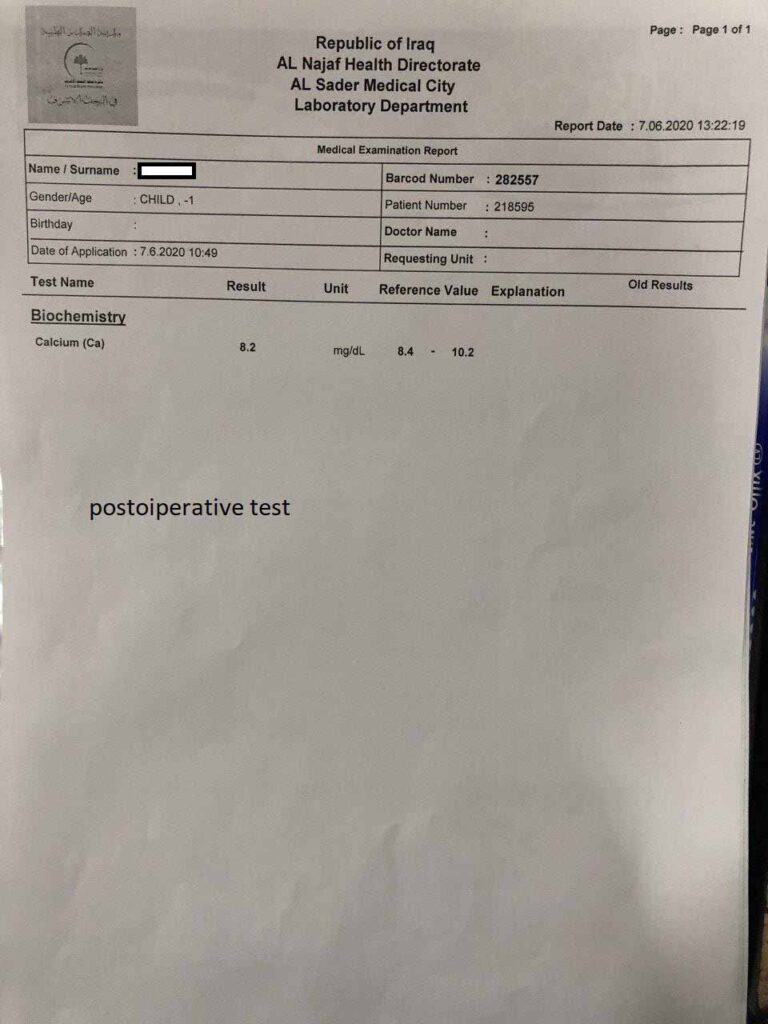

Significant drop of parathyroid hormone in 3rd postoperative day.

Review of literature

Giant parathyroid adenoma: a case report and review of the literature

Mohamed S. Al-Hassan, Menatalla Mekhaimar, Walid El Ansari, Adham Darweesh & Abdelrahman Abdelaal

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 13, Article number: 332 (2019)

Background

The normal parathyroid gland weighs approximately 50–70 mg. Parathyroid adenomas (PTAs) are usually small, measuring < 2 cm and weighing < 1 gm [1]. Giant PTAs (GPTAs), although rare, are most commonly defined as weighing > 3.5 gm, with some reports describing weights up to 110 gm [2, 3]. Both PTA and GPTA present with the syndrome of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT), the third most common endocrine disorder [4]. The pathophysiology of PHPT is autologous secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH) by one or more of the parathyroid glands [4]. Although PHPT can be caused by parathyroid hyperplasia or carcinoma, however, around 85% of cases of PHPT are due to PTAs, and the majority of these are because of solitary PTAs, of which GPTA comprise a small number [5].

To the best of our knowledge, this case report describes the first case in the Middle East of a patient with non-ectopic GPTA presenting with visible neck swelling. This case report also reviews the published literature to report on the clinical characteristics and typical presentation of GPTA as well as diagnosis and treatment.

Case presentation

A 52-year-old Indian woman was referred to our Surgical Endocrinology clinic at Hamad General Hospital in Doha, Qatar. She complained of a neck swelling and generalized fatigue. Laboratory results showed hypercalcemia and elevated PTH. Her past social, environmental, family, and employment history (housewife) were unremarkable. She did not smoke tobacco and never consumed alcohol. There was no past history of symptomatic kidney stones; however, a recent computed tomography (CT) scan of her abdomen and pelvis showed a 2 mm non-obstructing calculus in the lower pole calyx of her right kidney with no hydroureteronephrosis. Her past medical history indicated that she had dyslipidemia, controlled with medication; however, she was not on any other medication. On physical examination, a right-sided neck swelling was obvious on inspection; on palpation a mobile non-tender nodule could be felt, approximately 3 cm in size. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. A neurological examination was unremarkable. On admission, her pulse, blood pressure and temperature were normal.

Serology laboratory tests showed corrected calcium of 3.12 mmol/L, an intact PTH of 503 ng/L, vitamin D of 19.97 nmol/L, and normal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level. Her renal functions were within normal limits, serum creatinine was 67 μmol/L, and 24-hour urine calcium was 4.30 mmol/L per 24 hours. Her complete blood count (CBC) and liver laboratory findings were within normal limits. Microbiology laboratory tests were not deemed necessary.

Imaging investigations included an ultrasound of her neck that showed a complex nodule (4.1 × 2.3 cm) with solid and cystic components, and vascularity was observed in the mid to lower pole of her right thyroid gland (Fig. 1). A parathyroid Sestamibi scan revealed tracer concentration in the thyroid tissues with more intense focal uptake observed related to the lateral side of the right thyroid lobe (Fig. 2). A delayed scan revealed residual persistent uptake, corresponding to the initially described increased focal uptake seen on the early images. These Sestamibi findings were highly suggestive of a PTA. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) was done but was non-diagnostic.

Discussion

A 52-year-old woman presented with a visible palpable right-sided neck mass and generalized fatigue. Ultrasound showed a complex nodule with solid and cystic components, and a Sestamibi nuclear scan confirmed a GPTA. Focused surgical neck exploration was done and a GPTA weighing 7.7 gm was excised. This case of non-ectopic GPTA is unusual in that it presented mainly with visible palpable right-sided neck mass, which was large to the extent that the initial ultrasound suggested that it could be a thyroid nodule.

PTAs are well-reported tumors that cause PHPT. However, when their weight exceeds 3.5 gm, they are classified as GPTA [2]. Ours weighed 7.7 gm, and is considered a smaller GPTA in relation to other reported cases [7,8,9].

In terms of presentation, the classic presentation of PTA is with PHPT accompanied by recurrent kidney stones, and psychiatric, bone, and gastrointestinal symptoms [4]. However, this full constellation of symptoms is rarely seen nowadays due to the more frequent routine assessments of blood chemistries of patients presenting to hospital and clinics. Hence, such early detection has led to the majority of patients with PHPT now being identified early in the asymptomatic stage [4, 10]. However, our review of cases of GPTA published during the last 10 years (Table 1, 20 case reports, 22 patients with GPTA) shows that only two out of the 22 published cases were completely free of signs and symptoms of hypercalcemia [15, 17]. On the contrary, Table 1 suggests that most GPTAs presented symptomatically, ranging from vague bone/abdominal pain [5, 11, 18, 24] to more severe presentations, for example chronic depression, recurrent symptomatic kidney stones, and severe gastrointestinal symptoms [1, 9, 13, 14, 19,20,21,22]. Very rare presentations included hyperparathyroid crisis and acute pancreatitis [1, 10, 16]. Our current patient presented with neck swelling and generalized fatigue, and she had a silent kidney stone that was identified by abdominal CT, suggesting that GPTA generally presents symptomatically or with signs of hypercalcemia. This is probably related to the higher levels of calcium produced by the larger tumor mass.

In terms of physical examination, the majority of GPTAs in the neck had a visible and palpable mass in the neck [7, 11, 13, 14, 17, 19, 20, 24, 25]. Their large size is one of the reasons a clinician may suspect thyroid disease before reviewing the laboratory results, as palpable nodules are more common in the thyroid. In our case, a swelling was readily visible on inspection and palpable on physical examination.

As for diagnostic laboratory studies, GPTA investigations start with serum calcium and PTH and proceed to imaging for localization (Table 1). Hypercalcemia and elevated PTH are hallmarks of PHPT [4], in agreement with our review where all cases had elevated calcium and PTH laboratory values [18]. A positive correlation between the size of a PTA and preoperative PTH and calcium levels has also been reported [2, 26, 27]. Calva-Cerqueira et al. (2007) concluded that if preoperative PTH is > 232 ng/L, there is 95% likelihood of finding a PTA weighing > 250 mg [28]. This is valuable, as surgeons can have an idea of tumor size preoperatively. As for histopathology, although FNA cytology (FNA-C) is increasingly used in the diagnosis of parathyroid pathology [29], its limitation is that FNA-C cannot distinguish between different types of parathyroid disease [30]. Our preoperative FNA-C was non-diagnostic, similar to others where preoperative FNA-C was non-diagnostic [16].

In terms of imaging, localizing a GPTA is imperative to guide management. The most commonly used method is a combination of neck ultrasound and 99mTc-sestamibi scintigraphy (MIBI) scan. The limitation of neck ultrasound in GPTA is that it may not show the extent of a lesion; when the GPTA is ectopic, a neck ultrasound will show no finding [5]. In mediastinal GPTA, neck ultrasound only rules out a neck lesion but does not otherwise aid in localization [20,21,22]. In neck GPTA, the combination of a MIBI scan and neck ultrasound effectively localizes the GPTA and allows for guided neck exploration [27]. Ultrasound alone predicts GPTA location with 79% accuracy; combining ultrasound, MIBI, and CT increases the accuracy of localization to 82% [2]. We agree, as in our patient, that combining neck ultrasound and MIBI scan accurately localizes the GPTA preoperatively. MIBI scans are more likely to localize GPTA in patients with higher preoperative PTH and larger GPTA size; an adenoma correctly localized by MIBI has a 95% likelihood of weighing > 5.5 gm [28]. As for the location, in agreement with most studies, our GPTA was not ectopic [2]; however, Table 1 shows that the mediastinum is a common location for ectopic GPTAs, suggesting that such GPTAs arise in the inferior gland [31, 32].

For the management, the 2014 US National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for PTA management are either medical or surgical if it fulfills specific criteria [6]. As with all the cases in Table 1, our case fulfilled the symptoms and laboratory criteria for surgery. We undertook MIP, in agreement that it is the preferred procedure [19], and ioPTH monitoring, to confirm removal of the PTA before closure. Although the MIP/ioPTH combination is a gold-standard treatment, comparable outcomes of MIP with and without ioPTH monitoring have been reported [33], with some studies suggesting the benefit of ioPTH monitoring is only for patients with equivocal imaging [34]. This might be an important feature to consider when institutions seek resource utilization and cost savings. In agreement with the point that ioPTH might be beneficial only in equivocal imaging findings, ioPTH monitoring seems to have limited use in GPTA. Only in five instances was ioPTH monitoring undertaken [5, 13, 17, 19, 23] (Table 1), probably because preoperative imaging and intraoperative visualization in GPTA leave little doubt about the location [28], and because of a high likelihood of single gland disease [2]. At our institution, PTA standard intraoperative practice is ioPTH monitoring and frozen section to confirm excision.

Postoperatively, larger sized PTAs may be associated with a higher incidence of postoperative hypocalcemia [26]. Table 1 agrees with this, showing that hypocalcemia occurred in cases of larger GPTA. Hungry bone syndrome, a severe but rare form of postoperative hypocalcemia, occurred in four cases (Table 1), all of which had GPTAs weighing > 30 gm. Patients with smaller GPTAs were less likely to have postoperative hypocalcemia. Our patient presented with a 7.7 gm GPTA, considered a smaller GPTA in relation to other reported cases [7,8,9], which could explain why it had a less severe presentation as well as outcome after surgery compared with the other cases. Postoperatively, our patient, due to the smaller GPTA, became normocalcemic with normal PTH, and was not discharged on any calcium repletion therapy. Our patient was followed for a total of 3 years postoperatively and she remained asymptomatic and normocalcemic, without recurrence. This fits with outcomes reported in a study following patients for an average of 40 months, where all patients remained normocalcemic and there was no recurrence during this time, even in those with suspicious histologic features [27].